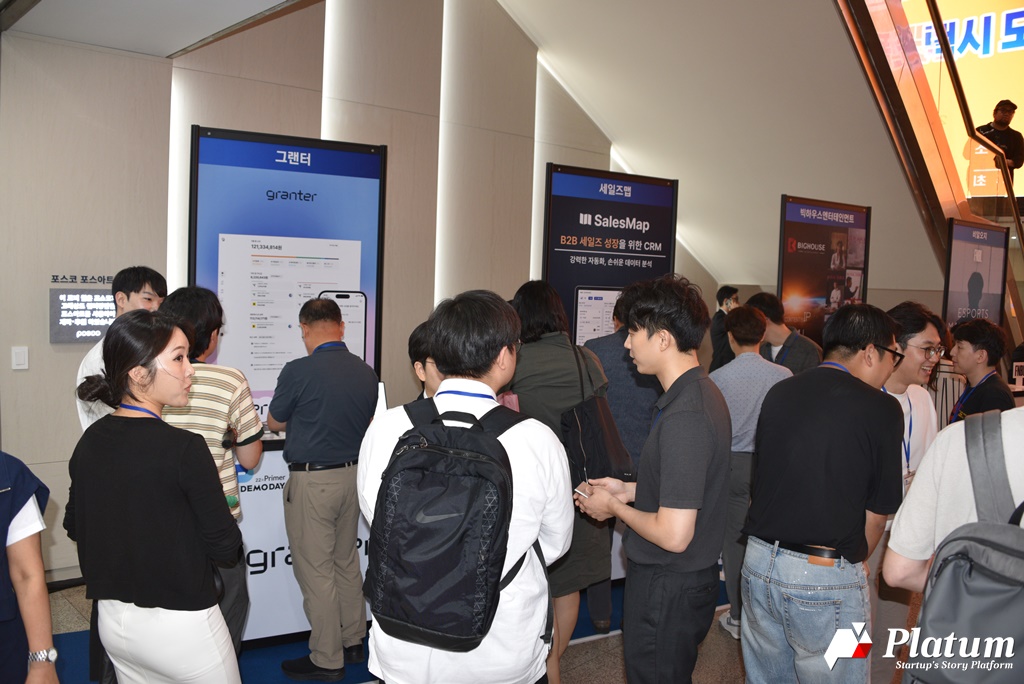

Startup accelerator ‘Primer(스타트업 액셀러레이터 ‘프라이머’)’ held Demoday (“22nd Batch”) on September 13 at the International Conference Hall of the Science and Technology Convention Center to present the business performance and future plans of the 12 startups it invested in and incubated in the first half of this year.

Primer, said to be the first accelerator in Korea, has been conducting batch recruitment and demoday since 2010 and has cumulatively invested in 262 startups. Primer’s major portfolio companies include Myrealtrip, Idus, Soomgo, Rael, Samjjeomsam (3.3), Bungaejangter, which exited in 2013, Dailyhotel, which was acquired by Yanolja, Hogangnono, which was acquired by Zigbang, Laftel, which was acquired by RIDI, and Styleshare, which was acquired by Musina.

While the IRs of the 12 startups were the main event of the day, the post-event Q&A session with the audience, moderated by Dokyun Kwon, CEO of Primer, Kiha Lee, CEO of Primer Sazze Partners, Kihong Bae, CEO of Strong Ventures, and Taejoon Rho, Partner of Primer, was a highlight. Over the course of an hour and a half, 14 questioners asked a variety of questions, including the accelerator’s investment perspective and when to go global. Most of the questioners were founders of early-stage startups.

Dokyun Kwon, CEO of Primer, emphasized that early-stage startups should focus on customers. “We invest in startups that have a business model that solves real people’s pain points, not imaginary ones,” he said, emphasizing that a business should start with customer needs, not features or technology.

Kihong Bae, CEO of Strong Ventures, said he looks at a small part of the founder when investing. “I’m not looking for big ambitions, I’m looking for everyday attitudes. The little things that come out of a person’s body and mouth without them realizing it. It may not seem like a big deal, but you can infer how the founder treats employees while running the company, how they treat investors, and how they treat future hires.”

Kiha Lee, CEO of Primer Sazze Partners, said what we look for in investing is people. “Products can change over the course of a business, but people don’t,” he said. The teams we’ve invested in that have leadership and tenacity have been successful.” When it comes to going global, he said, “You have to start from a local service perspective. Just changing the language doesn’t make it global.”

The full Q&A between Primer’s partners and the audience is below.

-It is a basic question, but what do investors or accelerators look for in a startup?

Dokyun Kwon (hereinafter referred to as Kwon): The business model is important. It shouldn’t be your own idea or something you imagine in a matrix, but something that is grounded in the real world and solves real people’s discomfort and specific problems for specific customers. Team and people skills can be learned in business, but if you start with the wrong model, it’s not easy to undo.

Kihong Bae (hereinafter referred to as Bae): It’s hard to say what we look for in a team, and there’s no right answer. But in general, I’m not in favor of one-person teams. The business environment is getting tougher, competition is getting tougher, and money is hard to come by. It’s not easy to survive alone in this environment. Therefore, I prefer to see teams with co-founders who have been working together for a long time.

Kiha Lee (hereinafter referred to as Lee): I mainly look at people, themselves. I think products can change over the course of a business, but people don’t change. Primer and Primer Sazze Partners have invested in more than 300 startups together, and the companies that have leadership and are really persistent are the ones that end up succeeding.

-How do you see the outlook for travel tech, and when it comes to providing platform services, do you need to attract customers first, or do you need to attract platform workers first, or do you need to do both?

Lee: I’ve invested in and vetted a lot of travel tech companies, and my opinion is that it’s very difficult to do business. There are a lot of variables, and things don’t go according to plan. Consumers use a service once, and if it doesn’t work right, they don’t use it again. There is a lot of work to be done to solve these problems. I think it’s better to be nimble and fast and work with smaller customers than to try to serve the masses from the beginning. It’s not about trying to be in every city, it’s about picking a city or a region.

Kwon: A common phrase that startups use in their business plans is, “We’re going to cater to our customers’ tastes and make it easy and convenient for them.” But they don’t realize how hard it is. It’s a very difficult task for a company to cater to the tastes of customers. It’s not easy to cater to a variety of different tastes. If you really want to cater to your customers, you can’t be too broad. You have to narrow it down and make it as comfortable as the tongue in your mouth. Many startups approach the market too broadly. Targeting a product like it’s a one-size-fits-all solution leads to too much trial and error.

Lee: The second question is about marketplaces and matchmakers. The platform business sounds easy, but it’s the hardest business. Most marketplaces and matchmakers have failed. Only Amazon, eBay, Airbnb, etc. survived and all the others disappeared. The reason is that you need to attract both sellers and buyers. If you want to increase your chances of success, you need to start meeting their needs in a small way. That’s how successful platforms like Jefferson and DoorDash grew.

-Do you look at the educational background of the founders when considering an investment?

Lee: Seed stage companies don’t have much to show externally, and they don’t have results or numbers to show because they’re just starting out. That’s why domestic and foreign VCs often look at the educational background of seed-stage companies and think it’s a good indicator of the company’s capabilities. If the founder has worked hard and graduated from a good university, they think it’s a sign of the team’s capabilities. So in the US, founders who graduated from Stanford or Harvard get almost 50% of the investment at the seed stage. But at the series stage, education doesn’t matter as much. From then on, everything is tied to performance, including revenue and growth.

Kwon: Different investment firms have different policies, but at Primer, we don’t look at education and age.

-Startups pivot when they don’t grow as expected. Do you make suggestions or wait for the founders to decide? If so, what metrics do you look at?

Bae: A few years ago I would pivot first, but now I don’t. That’s because in my 11 years as an investor, I’ve seen teams pivot and do well, but I’ve also seen teams take the same thing one step further and grow. I get asked a lot about when to pivot, and it’s really up to the founder.

This may be a different story, but you have to be very strong mentally and physically to do a lot of pivots. After every pivot, there’s a huge sense of failure and fear of the next one, and it’s very exhausting. So when I meet founders who are thinking about pivoting, I tell them to work out hard.

Kwon: There is no right answer. Different partners at Primer have different views. If the company is not on track, I actively recommend pivoting. Founders know that if things aren’t going as expected, they need to change. But psychologically, the regret of the past and the fear of the new delay the time. They know they should let go, but they don’t. But think about sunk costs. Startups have a certain threshold, a certain amount of debt, and a certain amount of time to exit or change their business. It’s not a good idea to keep going if there’s no clear customer response. Founders have to set the right threshold.

Lee: There are two types of pivots: one is to strengthen what’s working well, and the other is to change to something completely different. Examples of the former are Slack, Sendbird, and Twitter. But the latter is a really painful process.

-Is it right to think about the global market from the start? Many entrepreneurs vaguely believe that if they can just accumulate a lot of users, they can make money later, but is that the right approach?

Lee: Startups have no money, but they also have limited time, so one wrong decision can ruin years. One of the biggest mistakes is going global. A lot of startups that have reached a certain level of growth in Korea want to go global, especially in the US. But I haven’t seen many successful examples. This is because they try to go global with a service that is only for Koreans. Don’t think that you can go global just by switching to English. For example, if a Southeast Asian startup has a successful product in its home country and comes to Korea because it’s a slightly bigger market, it’s a completely different culture, there are more difficult consumers, and marketing costs are higher. The US market is more challenging than Korea. There is a pattern of allocating about 30 out of 100 resources when entering the U.S. It is the U.S. market where there is no guarantee of success even if you spend 100 out of 100.

How do you do it globally? The only way is to focus on local customers from the beginning. SendBird, Moloco and Noom are examples of companies that have done just that. All three of these companies had American customers as their first customers. The U.S. is a multi-ethnic country, so the products are very simple. So products that work in the U.S. also work in Europe and Asia. I would say that’s a characteristic of American companies. If a service works in the U.S. from day one, it can come to Korea later.

Taejoon Rho(hereinafter referred to as Rho): This is a real-life example: when I was at Danggen (which means carrot in Korean), a second-hand trading platform, I went to the UK and tried to go local. The bottom line is that we got beaten up. It was a challenge to get British consumers to understand that the Danggen app uses temperature as a rating for users manners or kindness. We had feedback that the Danggen (carrot) character was too Asian or too queer. I realized that it’s a very different market culturally.

Lee: If you have a lot of users, you can make money. But the approach is different depending on the type of customer. If it’s a B2B service, you can make money by charging from the beginning, but it’s hard to do that with B2C. If you think B2C is easy, it’s actually 10x or 100x harder than B2B because customers don’t want to pay for a service they used to get for free. B2C doesn’t make money just because you have more users.

-What criteria should I look for in someone to work with in the early stages of a startup, and are accelerators and investors willing to invest in internal ventures these days?

Lee: After 11 years of investing, I can tell if a company is going to be successful or not just by walking into the office. For example, if it’s a place where people are just waiting to leave, it’s never going to be successful. A few years ago, I went to the office to meet Jae-hyun Kim, CEO of Danggen Market, and even though it was during the pandemic, the employees were working really hard. It’s in the same vein as what I said earlier about seeing people. In the case of Pierrot Company (a subscription/installment service for refurbished devices, operator of ‘phoneGo’), which presented at the event today, they pitched several times and passed the primer batch after 5 attempts. This is because the team is desperate to make something impossible work well. The reality is that even companies that work this way are not sure of success. On the other hand, we don’t see that with in-house ventures. Of course, they may succeed beyond our expectations, but it’s hard to favor them at this point.

Kwon : In-house ventures have ownership issues. It is uncertain whether a startup will succeed or not even if you put 150% of your energy into it, but if the ownership is unclear, it becomes ambiguous. A big company with a system can work even if ownership is unclear, but it’s different for a startup where the only thing you have is your body. I think it’s difficult unless the founder is a major shareholder and can put everything on the line.

Bae: I have a slightly different opinion, but just because it’s an internal company doesn’t mean they’re not desperate or working hard. I think the bigger issue for investors is equity. If an internal company does well, it will be spun off or hived off, and it is important to know how much equity the parent company will have. Most Korean companies, especially large conglomerates, require at least 60% equity. For VCs, this means that there are very few exit opportunities. I think it’s up to the CEO of the startup to coordinate this. Even if it’s an internal venture, if the team is good and the parent company’s stake is 10% or less, I think it will be looked at without any problems.

When I look at people these days, I look at the little things rather than the big things. I look at their daily attitudes rather than their big ambitions. The little things that come out of your body and your mouth leak out without you realizing it. I met a founder, and he seemed good at first, but when I went to eat, I realized that his attitude toward the staff was very disrespectful. It didn’t seem like a big deal, but I realized it was indicative of how the founder would treat his employees while running the company, how he would treat investors, and how he would treat future hires.

Kwon: You don’t realize it, but the little things you do and say on a daily basis are often genuine and sincere. When you’re interviewing someone, you’re asking them an obvious question, and they’re using their reason to give you the right answer. This means you’re not a good interviewer. You should try to get them to talk as much as they normally do, and observe and judge the unconscious counts that come out.

-A startup is confident that they have a great product with great technology, but they are facing a funding barrier. What should they do?

Kwon: A common mistake that many early-stage startups make is that they leave out the customer when describing their business. Your business should start with your customers’ needs, not your features or technology. You need to understand what customers need, who they are, and what their situation is right now. VCs are always thinking about their investments, so if someone taps them on the shoulder, they talk about the company they invested in. Because that’s all we have in our heads. As I mentioned before, what he says or does unconsciously is his real heart and really means. You have to define what you’re doing from that point of view. You have to really think about it as a company that’s solving a specific problem for a customer, not a technology. In fact, when we’re mentoring companies that we’ve invested in, we hear a lot about features. Whenever that happens, I try to shift the conversation to how the product is working for the customer.

Bae: The best thing is to meet with investors who really understand the company’s technology. However, most investors probably don’t understand your business or technology as well as you do. If you want them to invest in you, you need to show them the results, such as sales.

Lee: You can’t just say your product is good, you have to find out if customers really want it. Dyson and Tesla are tech companies, but they succeeded because they spent a lot of money and a lot of time building something that customers really wanted.

-When you’re looking for seed funding, you’re obviously looking at a product. I’m wondering if the promise in the pitch deck is enough, or if it’s a requirement to see an actual MVP (minimum viable product)?

Rho: Most of the teams presented at this Demoday joined our Primer 22nd batch when they only had an early product and some customer traction. In the case of Granter (a service that makes it easy to manage business expenses with AI), we invested at the idea stage. We invested because there was a clear market problem, and we believed that if the team had the skills to build it, it could be a good service because it was a service that businesses needed.

Bae: Some investors think an MVP is essential, while others don’t think it’s important at the seed stage. Each investor has a different strategy and personality, so the perspective may be slightly different. The important thing is that entrepreneurs shouldn’t be influenced by such things. You just have to build what you want to build and prove it with numbers.

Lee: Instead, you have to be obsessed with the customer. You have to focus on what they really want. Toss didn’t have an MVP, they just had a landing page and people really liked it and signed up in droves and that’s when the real development started. You don’t have to have an MVP. The most important thing is that the product is something that real customers want. You don’t want your customers to live in your imagination. There are many tools available today that allow you to identify customers without an MVP. If you start with your own hypothesis and no customers respond, you’ve wasted your time and effort. It’s no use asking your friends. They’ll tell you it’s great. You need to get real customer feedback.

-I wonder if early-stage startups should prioritize generating revenue or growing their user base by offering their services for free, even if it means reducing their initial deficit. If the priority is to grow the user base first, at what point should the company focus on growing revenue?

Lee: I think you can do both. If it’s free, you can either look at the growth curve and start charging, or you can start charging a little bit and keep raising the price as your customers grow. But the important thing is that the customer wants it.

Kwon: What the founding team should be interested in is not the methodological approach, but making sure that real customers like your service. If you’re counting sideways to get paid, you’re losing the essence. It’s never too late to start marketing when you’re bigger. I think early startups should focus more on validating the hypothesis of the product.

-How do accelerators build founder capacity post-investment?

Rho: One of the key values that Primer provides is bringing together great startups and keeping them close to each other, so they can learn and grow from each other. It’s very hard to change or grow people to get things done, so it makes sense to start with people who are good at it in the first place. Investing is the same way.

Kwon: People don’t change, but they have to be educated. We try to point them in the right direction with good startup stories and content. But there are a lot of good startup models out there, but there is more noise. That’s why we often tell our portfolio companies to avoid founder hangouts and meetups. If you’re exposed to too much noise, your values get confused and you learn and apply the wrong things.

-Some startups look for unmet consumer needs. What kind of strategy does it take to target that market, and how does drinking affect your business?

Kwon: You can do good business even if you don’t drink. I guarantee it. When I was in business, I stopped having drinking parties related to dealer sales. At first, my salespeople complained about it, but after about a year, they actually liked it, and our sales increased.

Lee: I would approach drinking from the perspective of developing business skills. You can take an educational approach and read books, blogs and podcasts. It’s also good to have several mentors around you. It could be a fellow entrepreneur or someone who’s been there before. Steve Jobs had about four or five mentors that he would meet with once a quarter. You can get feedback from multiple people and make your own decisions. I think building that capacity will help you more than drinking.

Rho: The basic frame of reference would be to find customers and find out what percentage of those customers come back. It is said that a company can become a unicorn if it has more than 60% repeat purchases, and if it has a user base with 40% repeat purchases, it can become a big company that can survive. When I first saw the service Coupangeats proposed, I wondered who would use it, but when I tried it, I loved it. If you can find that space, it’s possible.

Bae: Most companies are doing what they already do faster, better and cheaper. I don’t know that there’s a whole new service that doesn’t exist. You have to think more deeply about whether it’s really something new, or whether there’s no market for it and they’re trying to force it, or whether it exists and the founder doesn’t know about it.

-Investors may have preconceived notions about certain industries. How do they or you break down those preconceptions?

Kwon: Of course, accelerators and investors can misjudge and be wrong. The metric that breaks that down is customer performance. No matter what investors say, if customers don’t like it, the service is wrong. Founders shouldn’t be influenced by what investors say. What they like doesn’t necessarily make a good service. You have to prove it with results, and if it doesn’t work, change direction. If you have your own metrics and show your investors the numbers on how customers are responding, they’ll usually agree.

-Customer feedback is that the product is good, but the price is high. How do we reconcile that?

Bae: If a customer sees a good product and doesn’t pay for it, it’s probably not a good product. The team probably set the price because they thought it was reasonable. But if customers don’t pay for it, then you haven’t built a product that they really want. You have to think more about whether it’s really a good product.

Kwon: That’s the difficulty of this business. It’s so hard to get a bill out of a customer’s pocket.

Lee: Usually, early-stage startups don’t have a very complete product. It’s common to raise the price as the product evolves. Do a lot of testing early on. For example, say you charge $10 for customer group A, $20 for customer group B, and $100 for customer group C. That’s how you balance the price points. These tests help you find the right price. That’s how you balance your pricing touchpoints.

-The growth rate of the company and the growth rate of the founder are not always the same. What advice do you have when you feel the growth rate is different?

Kwon : I think it’s best to start a company with the premise that when the company reaches a certain stage, you can become an obstacle in its path. When you feel that you have reached a critical mass, you should think about parting ways with the company. When I started, I didn’t know that INICIS or INITECH would become so big. At a certain level, I realized that I wasn’t the right person to run the company, so I left. Some founders run companies for decades while screaming “hungry”. They got ahead because they worked hard. Most company growth is capped at the founder’s level. The company only grows as fast as the founder.

Lee: As for the team members, it’s easy to bring in new people as the company grows, but it’s not so easy for the founder. Eventually, the founder will either leave or evolve and move up at the pace of the company.

Rho: When I meet with VCs and corporate people, they often ask me who the best founders are. Beom-seok Kim, CEO of Coupang, and Seung-gun Lee, CEO of Viva Republica, always come up. I don’t think they built such a big company by accident. I think it was possible because they operated while building their own capabilities.

Bae: If the founder grows faster than the company, he or she can keep the company for a long time. But sometimes the company grows faster than the founder. In the U.S., when there is such a gap, the board will remove the founder and bring in someone who is better. But in Korean culture, it’s hard to do that. I think it’s good to have a healthy board when the company is big enough.

Leave a Comment